Researchers are finding shrouded atmosphere time bombs—tremendous repositories of carbon dioxide and methane—dissipated under the ocean bottom over the planet. Also, the circuits are consuming.

Tops of solidified CO2 or methane, called hydrates, contain the powerful ozone-depleting substances, preventing them from getting away into the sea and environment. However, the sea is warming as carbon emanations proceed to rise, and researchers state the temperature of the seawater encompassing some hydrate tops is inside a couple of degrees of dissolving them.

That could be extremely, terrible. Carbon dioxide is the most widely recognized ozone harming substance, liable for around 75% of discharges. It can stay in the climate for a huge number of years. Methane, the primary segment of gaseous petrol, doesn't remain in the environment as long as CO2—around 12 years—yet it is, at any rate, multiple times progressively intense more than two decades.

The seas ingest 33% of mankind's carbon dioxide discharges and 90 percent of the overabundance heat created by expanded ozone harming substance emanations; it's the biggest carbon sink on earth. On the off chance that warming oceans dissolve hydrate tops, there's a peril that the seas will turn out to be large carbon producers rather, with grave ramifications for environmental change and ocean level ascent.

"On the off chance that that hydrate gets temperamental, in reality, dissolves, that colossal volume of CO2 will be discharged to the sea and in the long run the environment," says Lowell Stott, a paleoceanographer at the College of Southern California.

The revelation of these profound sea CO2 repositories, just as methane leaks nearer to shore, comes as driving researchers cautioned for this present month that the world is currently outperforming various atmosphere tipping focuses, with sea temperatures at record highs.

A couple of CO2 stores that have been found so far are found nearby aqueous vent fields in the profound sea. Be that as it may, the worldwide degree of such repositories stays obscure.

"It's a harbinger, maybe, of a territory of research that is extremely significant for us to examine, to discover what number of these sorts of stores are out there, how large they are, and that they are so helpless to discharging CO2 to the sea," Stott says. "We have completely thought little of the world's absolute carbon spending plan, which has significant ramifications."

Jeffrey Seewald, a senior researcher at Woods Opening Oceanographic Organization who thinks about the geochemistry of aqueous frameworks, scrutinized the extent of hydrate-topped supplies.

"I don't have the foggiest idea how all-around noteworthy they are as most aqueous frameworks that we are aware of are not related to huge gatherings of carbon, however, there's still a great deal to be investigated," he says. "So, I would be somewhat cautious about proposing that there are huge gatherings of CO2 that are simply holding back to be discharged."

Aqueous vent researcher Verena Tunnicliffe of the College of Victoria in Canada takes note of that information has been gathered at only 45 percent of known aqueous locales and most are not very much studied.

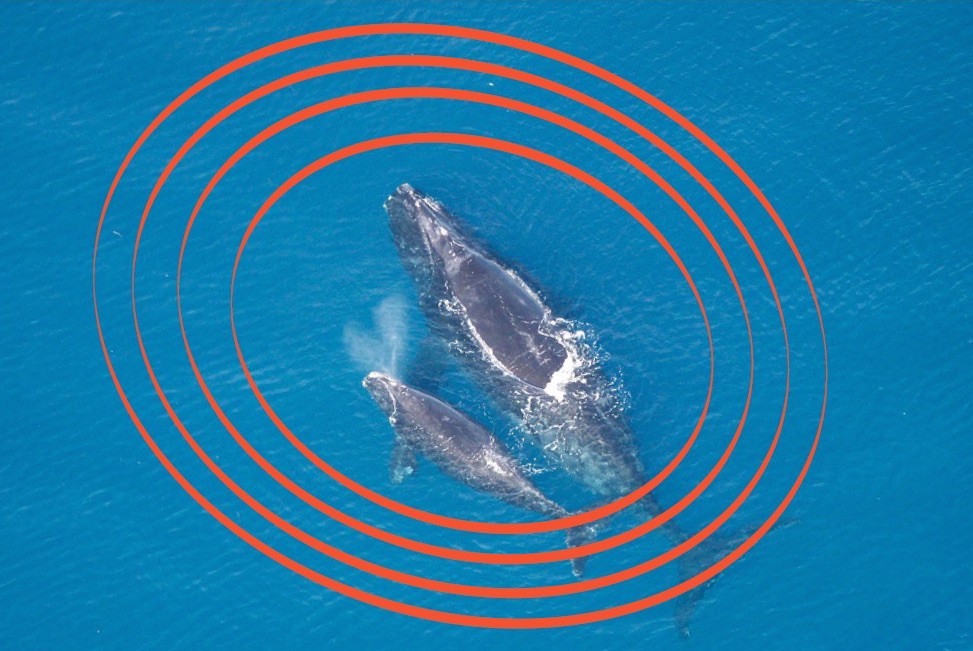

Different researchers are unmistakably increasingly worried about potential atmosphere time bombs a lot nearer to home—methane hydrates that structure on the shallower ocean bottom at the edges of landmasses.

For a certain something, there obviously is a great deal of them. Somewhere in the range of 2016 and 2018, for example, specialists at Oregon State College and the National Maritime and Air Organization (NOAA) sent another sonar system to find 1,000 methane leaks off the Pacific Northwest shoreline of the US.

Interestingly, only 100 had been distinguished among 2015 and the late 1980s, when researchers originally unearthed methane stores. There are likely a lot more to be found, given that starting in 2018, scientists just had mapped 38 percent of the ocean bottom between Washington State and Northern California.

"Since a ton of methane is put away on the mainland edges is generally shallow water, the impacts of sea warming will get to it sooner and possibly destabilize the methane hydrates that are available in the silt," says Dave Butterfield, a senior research researcher and aqueous vent master at NOAA's Pacific Marine Ecological Lab in Seattle.

He noticed that these methane leaks likely comprise a far bigger worldwide store of ozone harming substances than pools of carbon dioxide under the profound seafloor.

"This thought is that in the event that you destabilize the methane hydrates, that methane would be infused into the air and cause progressively extraordinary an Earth-wide temperature boost," says Butterfield, who in 2003 was a piece of an endeavor that found a hydrate-topped supply of fluid CO2 at an aqueous framework on the Mariana Curve in the Pacific.

Stott and partners recently distributed a paper exhibiting proof that the arrival of carbon dioxide from aqueous ocean bottom repositories in the eastern tropical Pacific about 20,000 years back helped trigger the finish of the last icy period. Also, in another paper, Stott finds land signs that during the finish of Pleistocene glaciations, carbon dioxide was discharged from ocean bottom repositories close to New Zealand.

The spike of climatic temperatures during past periods when ice ages were finishing mirrors the present fast ascent because of ozone-depleting substance outflows. While the seas have for quite some time been suspected as noteworthy supporters of antiquated a worldwide temperature alteration, the overarching agreement was that the CO2 was discharged from a layer of water resting somewhere down in the sea. Be that as it may, examine from Stott and different oceanographers over the previous decade focus to a geographical offender.

"Regardless of whether just a little level of the unsampled aqueous frameworks contain separate gas or fluid CO2 stages it could change the worldwide marine carbon spending plan significantly," Stott and his co-writers compose of present-day carbon supplies.

Take the hydrate-topped fluid CO2 supply found by Butterfield and his associates on a well of lava in the Pacific. They determined that the rate that fluid CO2 bubbles were getting away from the ocean bottom rose to 0.1 percent of the carbon dioxide radiated on the whole Mid-Sea Edge. That may appear to be a modest quantity, yet think about that the CO2 is getting away from a solitary, little site along with a 40,390-mile-long arrangement of submerged volcanoes that rings the planet.

Researchers accept such stores can be framed when volcanic magma far below the sea depths connects with seawater to deliver superheated liquids wealthy in carbon or methane that ascent toward the surface. At the point when that tuft slams into cooler water, an ice-like hydrate frames that trap the carbon or methane in the subsurface residue.

The hazard the repositories present relies upon their area and profundity. For instance, rising sea temperatures could in the coming years soften a hydrate topping a pool of fluid CO2 in the Okinawa Trough west of Japan, as per Stott. Be that as it may, the nonappearance of upwelling flows there implies a mass arrival of carbon dioxide at a profundity of 4,600 feet would almost certainly ferment the encompassing waters however not enter the climate for an incredibly significant time-frame.

Stott takes note of that discovering CO2 and methane repositories in the profound sea is a "needle and sheaf circumstance."

In any case, in a paper distributed in August, researchers from Japan and Indonesia uncovered that they had recognized five enormous and beforehand obscure CO2 or methane gas supplies under the ocean bottom in the Okinawa Trough by investigating seismic weight waves produced by an acoustical gadget. Since those waves travel more gradually through gas than solids under the ocean bottom, the specialists had the option to find the stores. The information demonstrates that hydrates are catching the gas.

"Our review territory isn't wide, so there could be more supplies outside of our overview zone," Takeshi Tsuji, a teacher of investigation geophysics at Kyushu College in Japan and a co-creator of the paper, says in an email.

"Methane or CO2 in this condition isn't steady, on account of escalated aqueous exercises in the hub of the Okinawa Trough. Along these lines, the CO2 or methane could be spilled to ocean bottom (and air)."